Cristina Monet – la poupée qui fait non

Cristina Monet – la poupée qui fait non

Back in 2014, obsessed with underdogs, as we were and proudly still are, we met Cristina Monet, who entrusted us with her private collection of pretty epic clothes to sell. As it sadly turns out, this is the last interview she gave. Why do we celebrate someone so instrumental but largely ignored in our cultural evolution after it’s too late? We should revere, celebrate and reward the Cristina’s of the world more publicly while we can still be guided and inspired by them.

By Colleen Nika

Three decades before Lana Del Rey waltzed on the grave of the pop mainstream and hit #1 singing about submission and death — and finding freedom through submission and death — Cristina Monet-Palaci was outsider pop’s patron saint, churning out danceable hymns of mortality and mistresses. Like Lana, she dabbled in the discomfiting suspension between artifice and acid observation. Both approach women’s dress-up as a form of drag. And like Del Rey, Cristina is a genre unto herself, a sui generis talent floating among prestigious peers but too contradictory to belong to anyone for long. Of course, the world wasn’t ready for Cristina’s queasy vision of life, sex, and love in 1980. Pop music was in its big and bland Reaganomics phase, and downtown NYC ‘s subversion du jour largely embraced the outwardly grotesque.

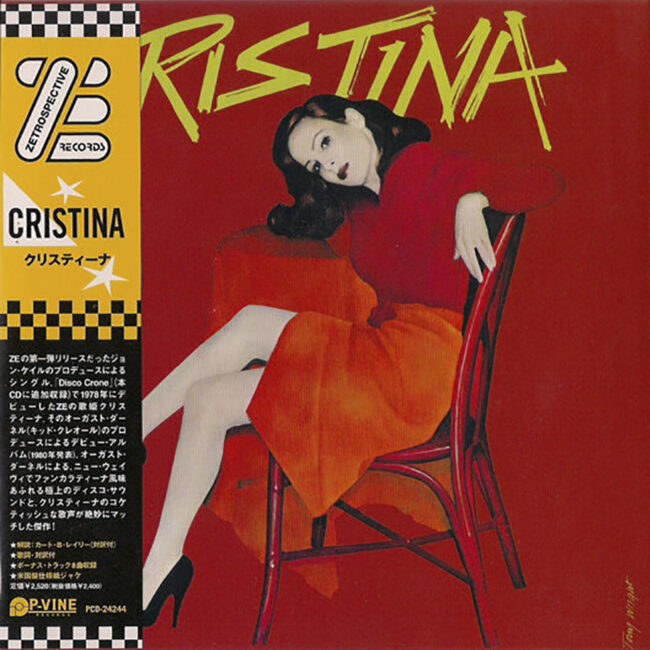

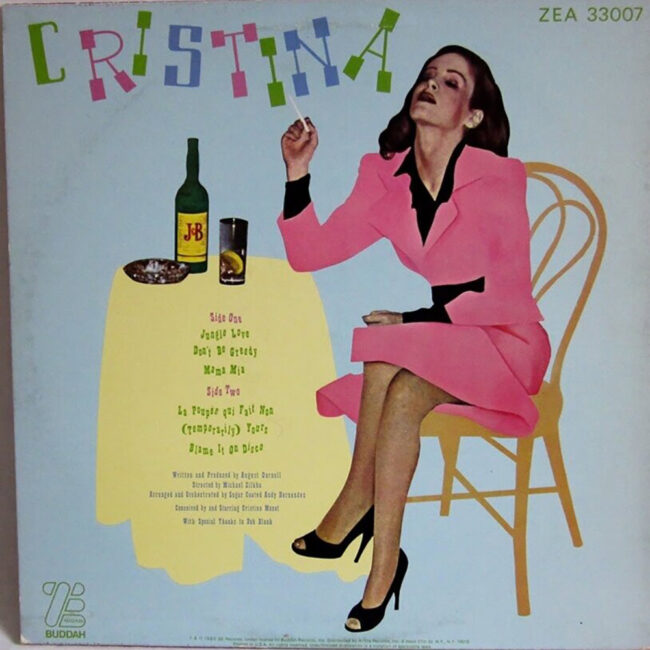

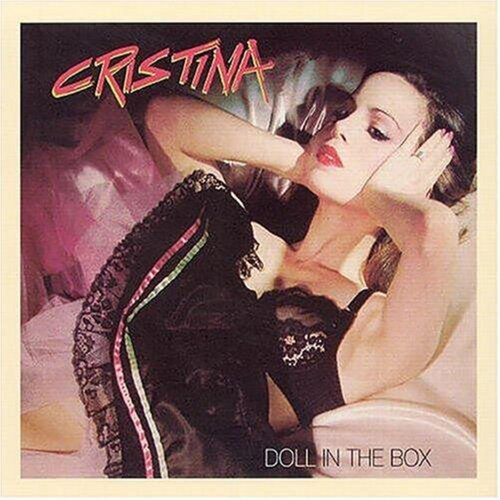

Amidst the piss, filth, and noise of the CBGB’s scene, Cristina’s complex couture pop (and accompanying uptown Chloé and Norma Kamali wardrobe) was an odd fit. Her debut album, later re-released as Doll In The Box, may have had surface similarities to the no wave, mutant disco, and freestyle movements, but that was largely due to context: it was produced by King Creole & The Coconuts founder August Darnell and released on future husband’s Michael Zilkha’s resplendent, extra-experimental label ZE Records.

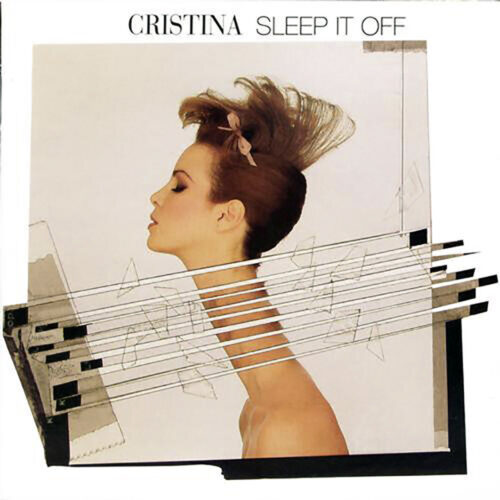

It attracted the requisite buzz, but Cristina, a drama kid with Freudian parental roots and a passion for Brechtian theatre, wasn’t particularly interested in becoming a zany pin-up for the Paradise Garage set. So, for her next album, she took the reigns and delved into even headier territory. Take “He Dines Out On Death,” a song about a man who gets lucky at his girlfriend’s suicide. “Let’s throw him a party, he Must be in hell,” she sings drolly. It’s a Nico-esque dirge, amidst her eclectic and undervalued second and final album, Sleep It Off, her true masterpiece and the final gasp from ZE. Then? She disappeared. Her moment was brief, bright — gone. Or so downtown NYC lore would assume.

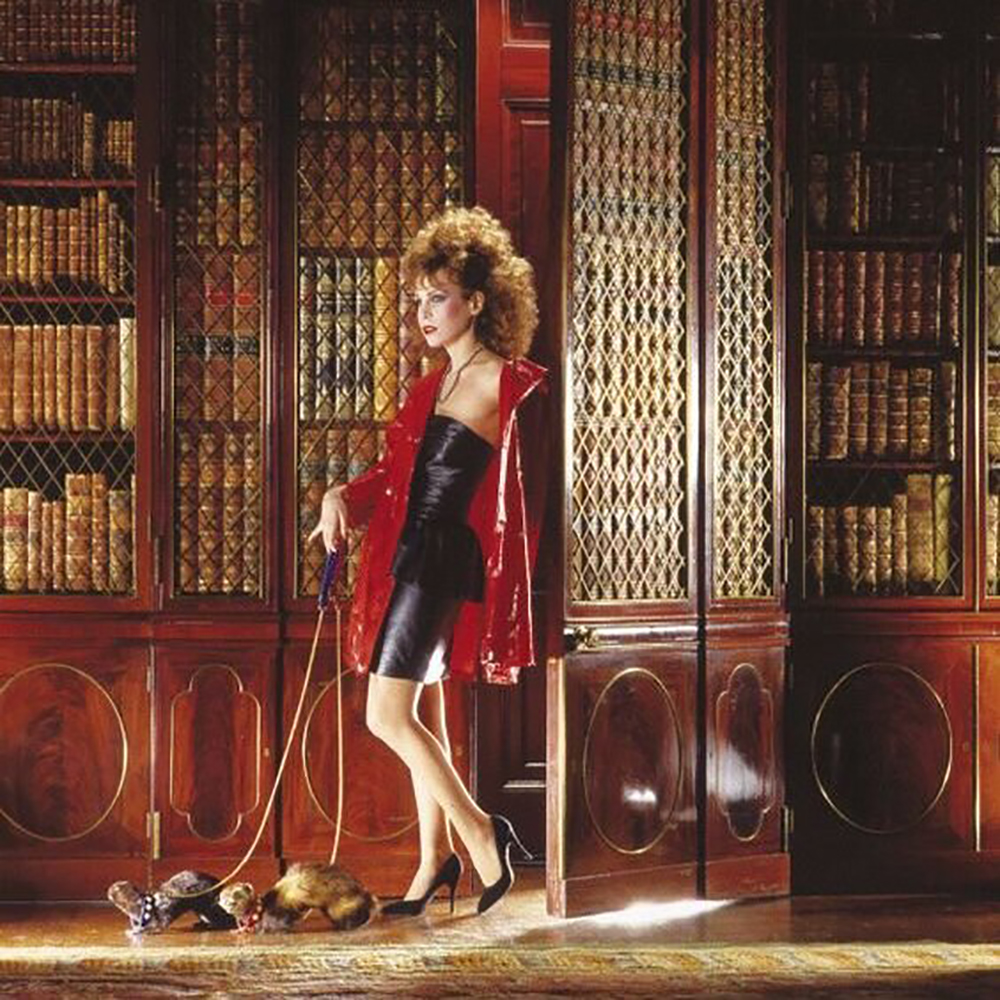

The truth is much less drastic, but far, far stranger. Cristina simply married Zilkha, had a girl named Lulu on Christmas Day, and pulled up stakes to move to Texas. Life happened, essentially, and her legacy of strange pop, lyrical provocation and excellent outfits soon settled into permanent cult legend. “I felt like Madame Bovary of the freeway,” she’s said of the regional cultural shock. Three decades later, Cristina is back in New York City, still fascinating, still contradictory, still glamorous — even after years of fighting a mysterious illness. Having donated some key pieces from her beloved couture collection to Byronesque (“it was like losing a limb!” she says), Cristina invited me to her flat for a chat. I was already a fan of those two albums but unsure what to expect in 2014. It turns out Cristina holds court exactly the way I had hoped — in a marvelously decadent, but darkly poetic Upper East Side apartment ruled by her five restless cats. We talked about her ‘bruised doll’ glamour, the slippery myth of NYC and if her downtown rival Madonna ‘dressed up’ her image in Cristina’s signature style moves.

Colleen: Back to the start: how did you go from dropping out of Harvard to working for the Village Voice to recording a debut record — all within a year or so?

Cristina: I grew up here and in Europe. I went to The Royal Central School of Speech & Drama, because I wanted to be a classical stage actress. And there was an exchange, since there’s no real tradition of that here. So, I went the other way; Harvard didn’t have a drama department. And then I took a year off, and had to find something to do with that year off. At Harvard, I did History Lit first, Theatre second. The Village Voice owner Clay Felkin gave me an apprenticeship off-off-off-OFF! Broadway theatre critic. That’s how I met Michael [Zilkha]. He bragged to someone at a drinks party: “I’m the youngest critic!” And she said: “No, you’re not!” And soon he called me up. And so it went! On our second date, we went and reviewed When You Coming Back, Red Ryder? in East Orange.

Colleen: Did you discuss music?

Cristina: Not really. We talked about Balzac. He said something to me that at 18 sounded very cool, but he probably had been rehearsing it. “In an age of frozen food and force-fed meat, Harold Robbins is the 8th grade Balzac of an 8th rate age!”

Colleen: Were you led to music by default? Were you a musical kid?

Cristina: Well, I was obsessed with opera as a kid, and I drew a lot. Michael loved to go to CBGB’s and I’d go with him. I liked the Sex Pistols, and the Velvet Underground, and I knew some of them from growing up here. But you know: I liked Brecht and Kurt Weill, which I got Michael into.

Colleen: That interest in Brechtian theatre really distinguished you from anyone else on ZE Records — or anyone in music at that time.

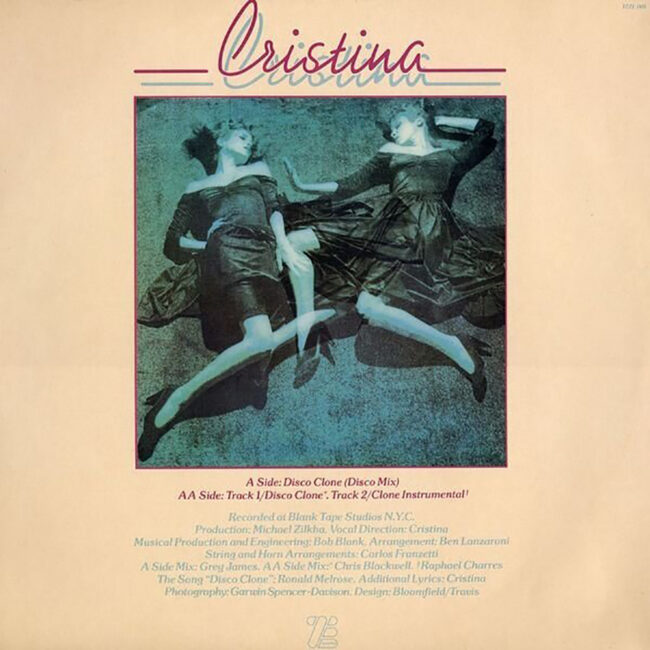

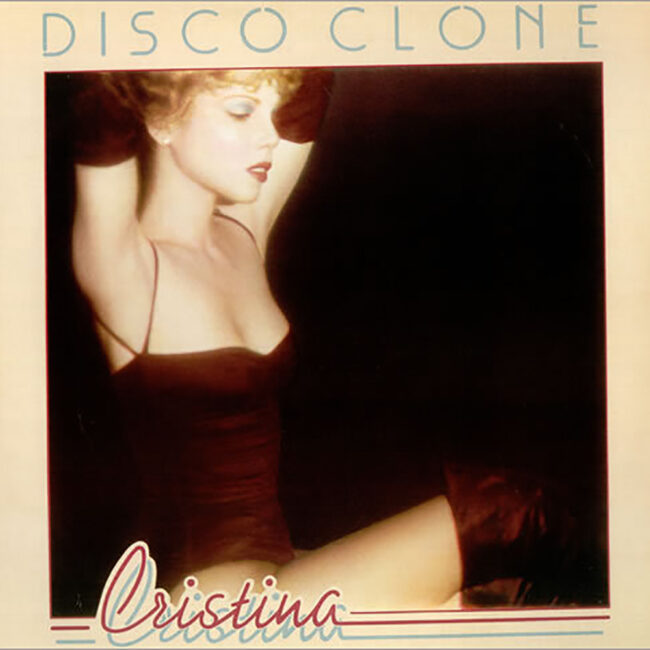

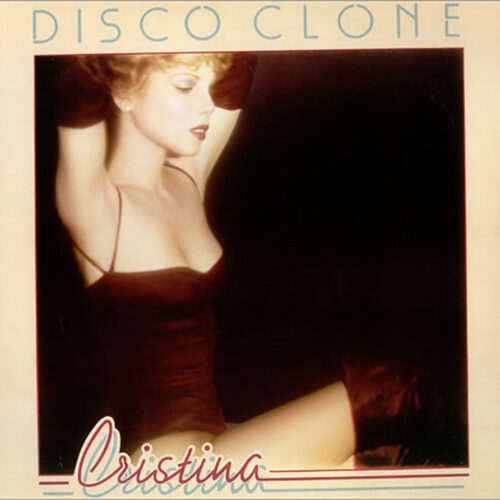

Cristina: I thought that the only way my debut single ‘Disco Clone’ could work was as a pastiche. And Michael said,“well, do you want to have a go?” So I did. And you know how every college has one dickhead who wears a ruffled tuxedo shirt to his own undergraduate opening of his dark little play? Ronald Melrose was that guy. And he directed me in something at Harvard: Man-In-The-Moon Marigolds [sic] or something. Anyway, he thought Disco Clone was a ‘really sexy song.’ So, the actor Kevin Kline and I took the piss out of that vocally. I said to him, “Hey, want to make some money?” [laughs]

Colleen: I can’t keep track of all the versions of that single.

Cristina: [Laughs] Michael had a father who gave him enough rope to hang himself with his trust fund. ZE Records was brilliant but he had no business acumen. It was the most expensive single ever made. John Cale, Nile Rodgers, everyone had a go. I thought his taste was really interesting. But I couldn’t believe he bought that record.

Colleen: How did that lead to the actual debut full-length?

Cristina: August Darnell was hired for the first album, but on the back of that, he created King Creole + The Coconuts. When we were working on the debut, later called Doll In The Box, I said that disco was really humorless — that chooga-chooga beat! Lugubrious. I didn’t mind Love to Love You Baby. But you couldn’t dance to it [mimics disco beat]. And I didn’t like John Travolta’s moves! I liked Latin beats. It’s sort of obvious now. I loved things like The Bangles. So, I asked August for Latin beats, and we had fun. I used to call him Rat Poison in Spats. He formed King Creole + The Coconuts at that time. I used to say he knocked them all up at once! He was very bright and evolved his own sound through our music and lyrics. But then, we tried to play live together, and it was stupid, because ‘never the twain shall meet.’ I was sort of sandwiched in.

Colleen: How did you feel on stage?

Cristina: I didn’t like it. To have King Creole back my weird live stuff? I should have had my own band. I felt silly. Three girls in leopard bikinis and this whole brouhaha! It was sort of stupid.

Colleen: It was probably difficult to know how to position yourself.

Cristina: I like old Cabaret music and I wanted to work with people organically. I wanted a Joe’s Pub atmosphere and an intimacy with the audience.

Colleen: Your rare performance of The Beatles’ ‘Drive My Car’ does feature your vocals in an almost camp, cabaret manner.

Cristina: It’s terrible, though. That video was just for television. I just sat and lip-synched on a car. It was so boring.

Colleen: Well, I mainly found the cover choice interesting. Jokey as well.

Cristina: Oh, I liked that part of it. I recorded it with Stony Browder, August’s brother. We did it as a swing, a real Marilyn [Monroe] swing. So, that video’s atrocious but I like listening to it!

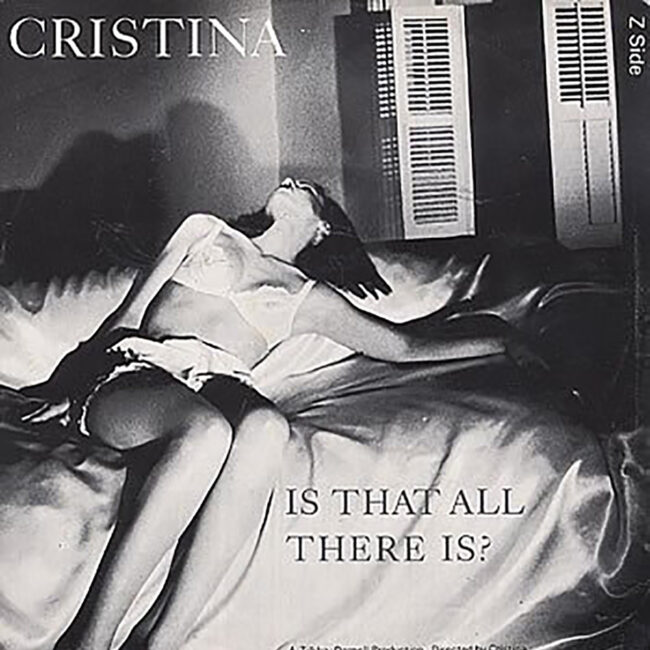

Colleen: What about ‘Is That All There is?’

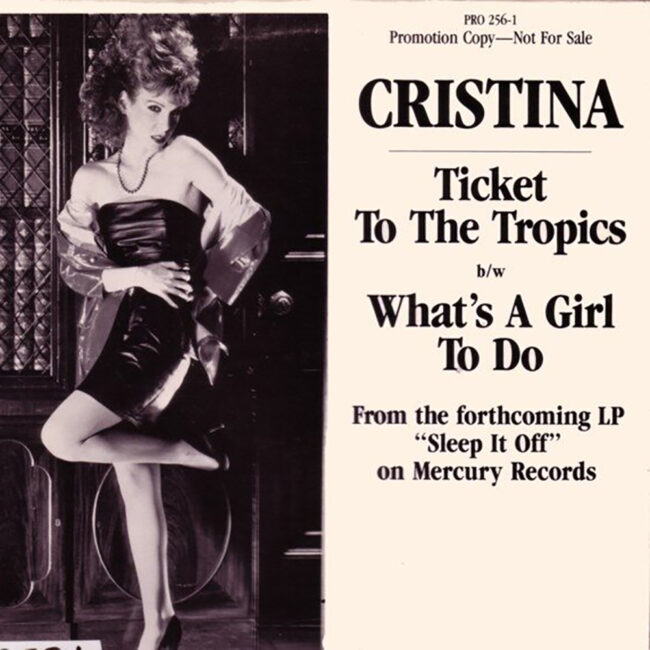

Cristina: Someone recently sent me a version of MY version by a gay Puerto Rican guy. August thought it was a good idea to do a punk version of that song. And as a classical actress, I do improv. But I said you can’t get disillusioned at the circus in 1984 or whatever the original lyric was. I just made it my own and recorded it in one take. It was a huge hit in minutes — it was the most requested song on BBC1 within weeks. And then the song’s writers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller joined in; they didn’t like my version and it stalled progress. You always think you’ll have another hit. It was logical to think that “What’s a Girl To Do?” would be a hit, but that was it! I never had another hit.

Colleen: You were pretty clearly ahead of its time and playing with a lot of contradictions in your music. Did your peers understand your vision?

Cristina: I had a good relationship with Ze Records. And I got on very well with the sound engineers or — as the English would say — working class people like lumberjacks in Detroit who loved my version of ‘The Ballad of Immoral Earnings’. But the American music critics at the time were very snide to anyone who wasn’t consciously downmarket. They thought I was ‘deb’. I didn’t have that problem in Europe. People understood the irony.

Colleen: Did you find any kindred spirits in the scene?

Cristina: Until I did Sleep It Off, I felt a bit…not bogus, but I was a theatre person. I knew what I was doing made sense to me, and there were people I liked — Talking Heads, Nico, Velvet Underground — that logically were in the same key as I what I did, but my work didn’t find a niche. I used to think that doing the record would lead to opportunities in theatre, but that’s not how it works. I didn’t have the commercial viability. Success bred success in those days. And there was a sense of dues needing to be paid; I didn’t feel I’d paid them. I always had a certain guilt. The boss’s girlfriend kind of thing.

Colleen: What about when you released Sleep It Off?

Cristina: Sleep It Off was a logical build. My mother always said, ‘you’re a brilliant writer and a genius artist.’ But no one ever said ‘oh, you can sing.” So, when I wrote lyrics they didn’t come with any expectation that had been thrown at me my entire life. It was something I was not supposed to be able to do at all, so there was no performance anxiety. But then I ended up really happy with it. You have to love what you do first, irrespective of whether it cuts the mustard. I know I put a lot of effort from the heart into those songs. It may have not been a hit record, but I still stand by them. They don’t embarrass me. I find those songs intelligent.

Colleen: It’s so jarring that you just released these two great records, then disappeared. Have you ever thought about a comeback?

Cristina: I did a collaboration with Ursula 1000 a few years back, and there was talk of doing a record. . I have an unreleased record — I’ll Die Laughing. In 2007, I was going to make it in France with [Michel] Esteban. Now he’s high-tailed it to South America! And I have a great song that I never released that I want to place. It’s the only song I ever wrote for a man, which I adore. It’s called “Where Am I Sleeping Tonight?” It was written for my then-boyfriend, Ben Brierley, who was my bass-guitarist. With a few lyric tweaks, it could be for anyone. It’s about a guy who goes from his Mayfair or Park Ave. girlfriend’s to his ex-wife’s to his parents’, who have emptied out his room, to his flat, where he’s emptied his ashtrays. It’s fun, it’s upbeat. It needs a good melody. It’s not somber and lugubrious.

Colleen: How did your father’s Freudian roots and mother’s playwright roots affect your own creativity?

Cristina: That’s a good question. My mother was considered the elder Marilyn Monroe. They were friends, actually, and they were both Catholic abused orphans who fucked their way through the New York psychoanalytic circle and group theatre. So, I was inundated with this stuff. My father was in France — and his narcissism was just terrible. [Chuckles.] He was chummy with Heinz Kohut from university days in Heidelberg and medical school in Austria. So, he substitutes the narcissistic profile for the libidinous profile. I love my father, but I mainly spent time with him at the tailor. But I was interested in his work. I read a lot of things about Shakespeare. All sorts of grandiosity and self-loathing. And I suppose Freud was a genius in a similar way. That sort of morbid introspection — I have a lot of that! My mother was a nightmare when I was a kid, and would say: “There’s nothing that can’t be transcended by scorn,” which Camus said. Or “You have to be the captain of your own fate.” You tell that to a four-year-old, and what are they going to do? I’ve been crashing my bark into the rocks! [Laughs] I used to say I was Tennessee Williams without the genius or gender, only the mother!

Colleen: Was your mother the one who introduced you to Brecht?

Cristina: No, that was one of my first boyfriends. He was one of Brecht’s bright young things, but was 47 when I met him. He was a Structuralist and I was a Lolita from hell!

I ran into her [Madonna] in more affluent circles, actually. On Park Avenue. She looked very different in those days! [Laughs.] And I wrote a piece on her actually, for my column: the New York Notebook for the London Literary Review. It was called The Canonization of Sleaze, and it was 1982. I compared Caravaggio and Desperately Seeking Susan, and I wasn’t very flattering about Madonna.

Colleen: You also have a strong visual legacy. What are your influences?

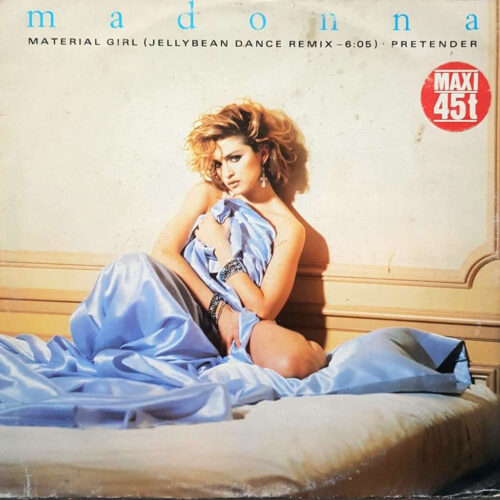

Cristina: I love fashion and theatre. I was styling myself at six years old, wearing a Madame de Pompadour costume. I had strange tastes! I used to sneak out and go to Norma Kamali’s little shop on 64th Street. I always had a sense of costume, maybe due to my childhood obsession with opera. I was short so I had to be distinct. I wore Queen Mother handbags, Brigitte Bardot hair, and Frederick’s of Hollywood heels — prostitute shoes. That was my look! And that was well before I recorded anything. It was slightly S&M. I had very white skin and small bones, and played up that whole baby doll thing even before I worked with Guy Bourdin as underwear model. In some ways, I felt like I was a drag queen, in the Tennessee Williams heroine sense. I felt a bit androgynous.

Colleen: What was your relationship with Bourdin?

Cristina: He was like Helmut Newton, but the opposite end of the spectrum. He’d call me The Bruised Baby Doll in those days. I had very distinct ideas about how I wanted to present myself. Madonna didn’t do a lacy underwear cover until I did, then she said, “I didn’t crib from Cristina!”

Colleen: The literal meaning of negligee is “neglected” — and your artwork in particular tends to subvert the usual sexy imagery of a woman in lingerie.

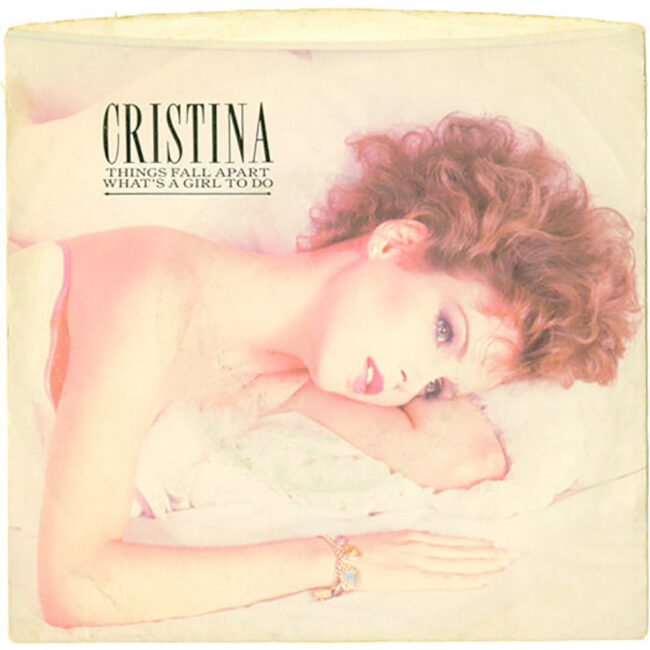

Cristina: I wanted the cover of ‘Is That All There Is’ to resemble a suicide. A grainy look, like those early Sixties British films, like Darling with Julie Christie. And I wanted a Lauren Bacall look for the first album, but I’m a bit short for Lauren! It was a pink Chloé haute couture suit. I wanted to include a visual reference to old movies like King Kong. There’s some lines on that first record, like in ‘Blame It On Disco’, that have that Bacall quality. The ‘Disco Clone’ cover was my Norma Kamali disco dress.

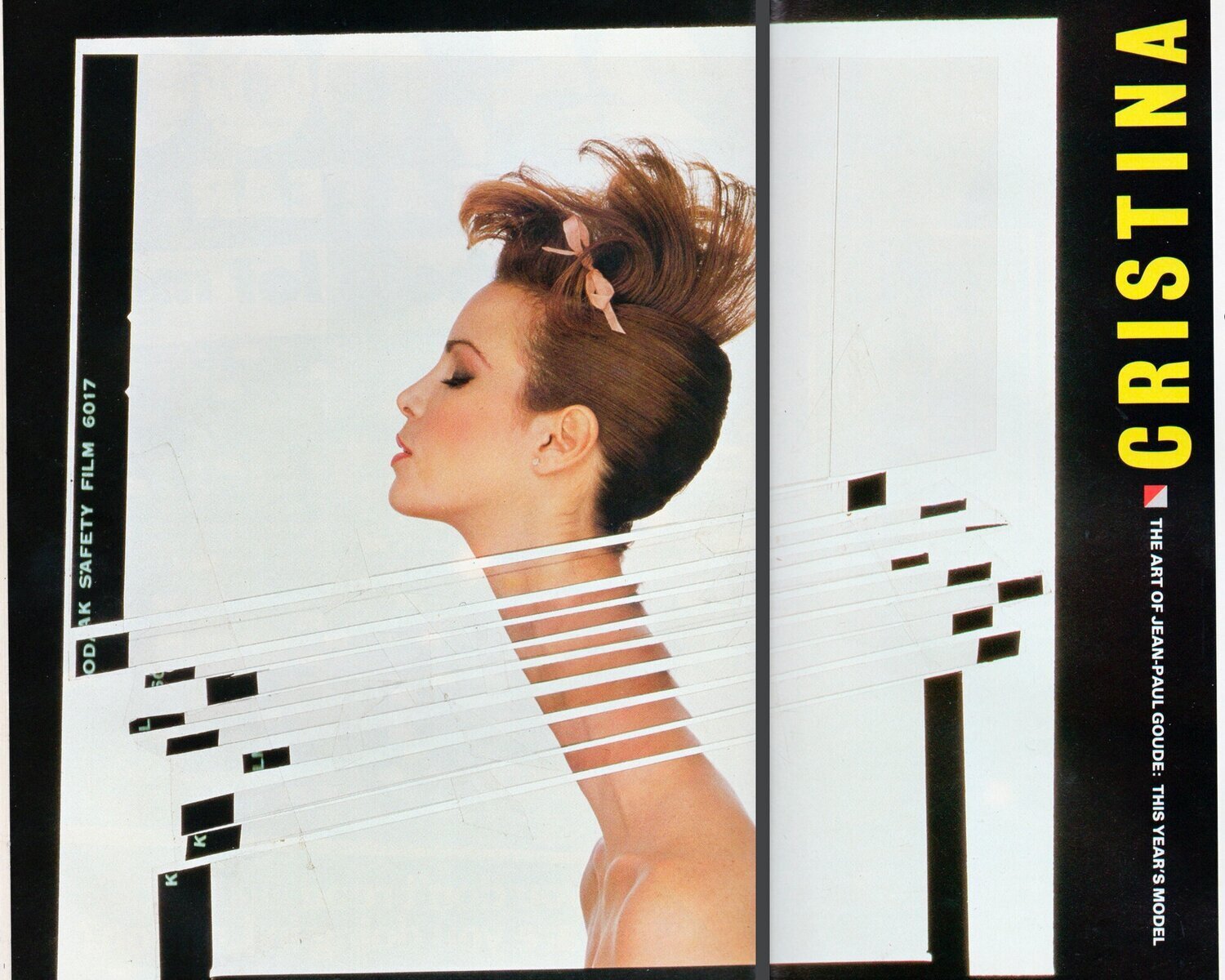

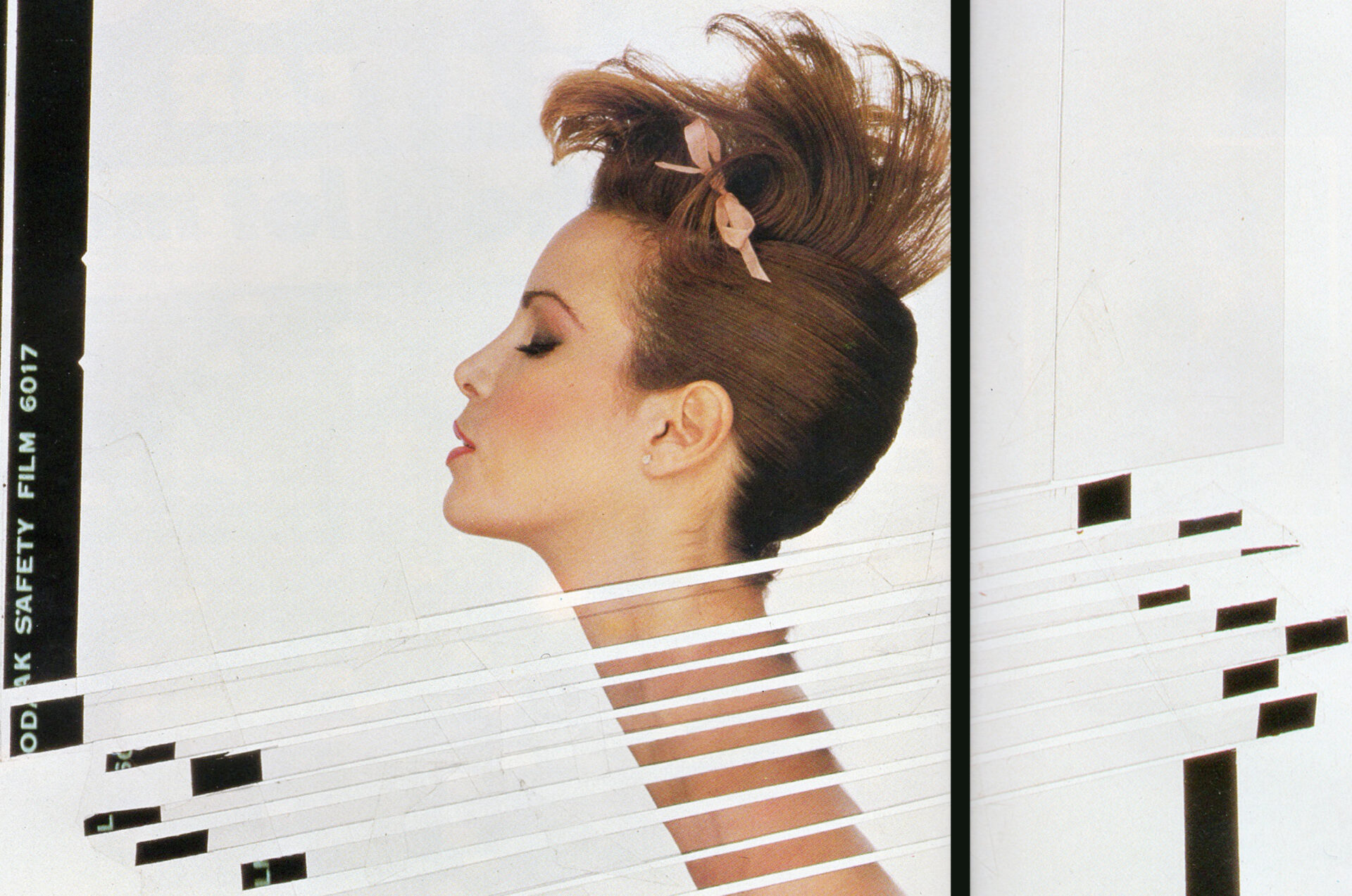

Colleen: Sleep It Off is quite a departure, obviously musically, but also visually. Was that Jean-Paul Goude’s influence?

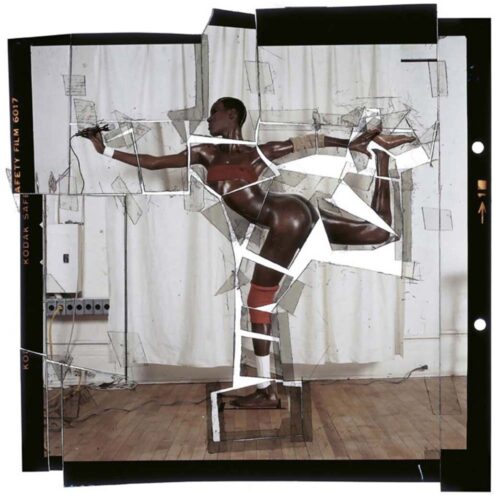

Cristina: Sleep It Off is an ambiguous cover. Didn’t Goude recycle that idea with Grace?

Colleen: It has that same ‘pop vivisection’ feel.

Cristina: Maybe because Grace Jones was on Island Records, too. Jean used to say he shot the ultimate large black woman in Grace Jones and that I was going to be the ultimate small white woman. I took objection to that!

Colleen: It seems you did covertly influence a lot of people. Including, as you said, Madonna. How did you feel about being both her peer and her antithesis?

Cristina:We had a little bit of a friction. Back then she wrote “Dress You Up,” I said it was about me, and then she started doing cinematic underwear photo shoots a la mine. But she’s a great entertainer. A powerhouse. I don’t like Barbra Streisand. Maybe it’s sour grapes because I don’t have a great voice, but it’s never been my thing. So, I’d take Madonna over her.

Colleen: Did you ever run into her downtown, at parties and such?

Cristina: I ran into her in more affluent circles, actually. On Park Avenue. She looked very different in those days! [Laughs.] And I wrote a piece on her actually, for my column: the New York Notebook for the London Literary Review. It was called The Canonization of Sleaze, and it was 1982. I compared Caravaggio and Desperately Seeking Susan, and I wasn’t very flattering about Madonna.

Colleen: Did she read it?

Cristina: Well, I should hope so — it was the London Literary Review. [Laughs.] No. She had no reason to give a rat’s ass!

Colleen: Any special memories of the couture outfits you donated to Byronesque?

Cristina: I remember every one of those outfits. Giving them up was like cutting off a limb. I wore all Alaïa for awhile. I was very particular. And a friend of mine, Bob Evans, made all my evening gowns, which were tiny. I had an 18-inch waist!

Colleen: What’s something you’ve learned the hard way?

Cristina: You don’t realize how narcissistic you are ‘til you lose it. Then again, some people never had it. I’ve had this bloody autoimmune illness the past few years. With cancer, everyone is interested in how you’re doing. With this, you just get more and more isolated. And you lose your looks.

Colleen: Did you feel that NYC’s reputation as a counter-cultural centre was well-earned?

Cristina:I never gave it any thought. I certainly thought the music and art scene’s reputation was well-earned. The theatre scene was always infinitely better in Berlin and London. But New York more of a suburban shopping mall now. I haven’t traveled to other cities I love since 2006 or 2007, so I don’t have a means of comparing New York to them now. It definitely was a professional-class city when I was growing up here, but you could feel like the world was your oyster. Things like good wine hadn’t yet been preempted by stockbrokers. So, I’d say it doesn’t have the excitement it used to be. Or maybe it does for young people. What do you think?

Colleen: I think it’s like a suburban shopping mall.

Cristina: [Laughs.]

Colleen: Your Texas years are rather mysterious. What led you there?

Cristina: My father-in-law made us move there. So then I had to adapt to life as this sort of society hostess, Southern bride type and it was NOT me. I didn’t properly know America. I knew Europe. This sort of Southwestern city was a shock to me. It was like 1876. I parodied the whole culture in a piece I wrote called Gold Diggers ’88. The experience was like Lady Macbeth reincarnated: I’d be at a palace-sized mansion for a dinner party. I’d walk because I didn’t drive, but everyone would drive their Mercedes down two houses. I’d wear Alaïa and they’d look at me like an alien in their matching Judith Leiber handbags. They’d turn down the thermostat and put on the Valentino full-length, even if it was 120 degrees outside! And I thought you’d just wear a cotton dress. It was wild. Ours was the Abercrombie house — I had an awful time selling it. It was built in 1929 or something; where I’m from, that’s not very old. But I can tell you that when it was over, it was not a pleasant feeling when everyone kisses your ass and then closes ranks against you