Happy Ending.

The Beginning of MACHINE-A

Happy Ending.

The Beginning of MACHINE-A

The beginning of MACHINE-A

Interview by Gill Linton

Polaroids by Justin Westover

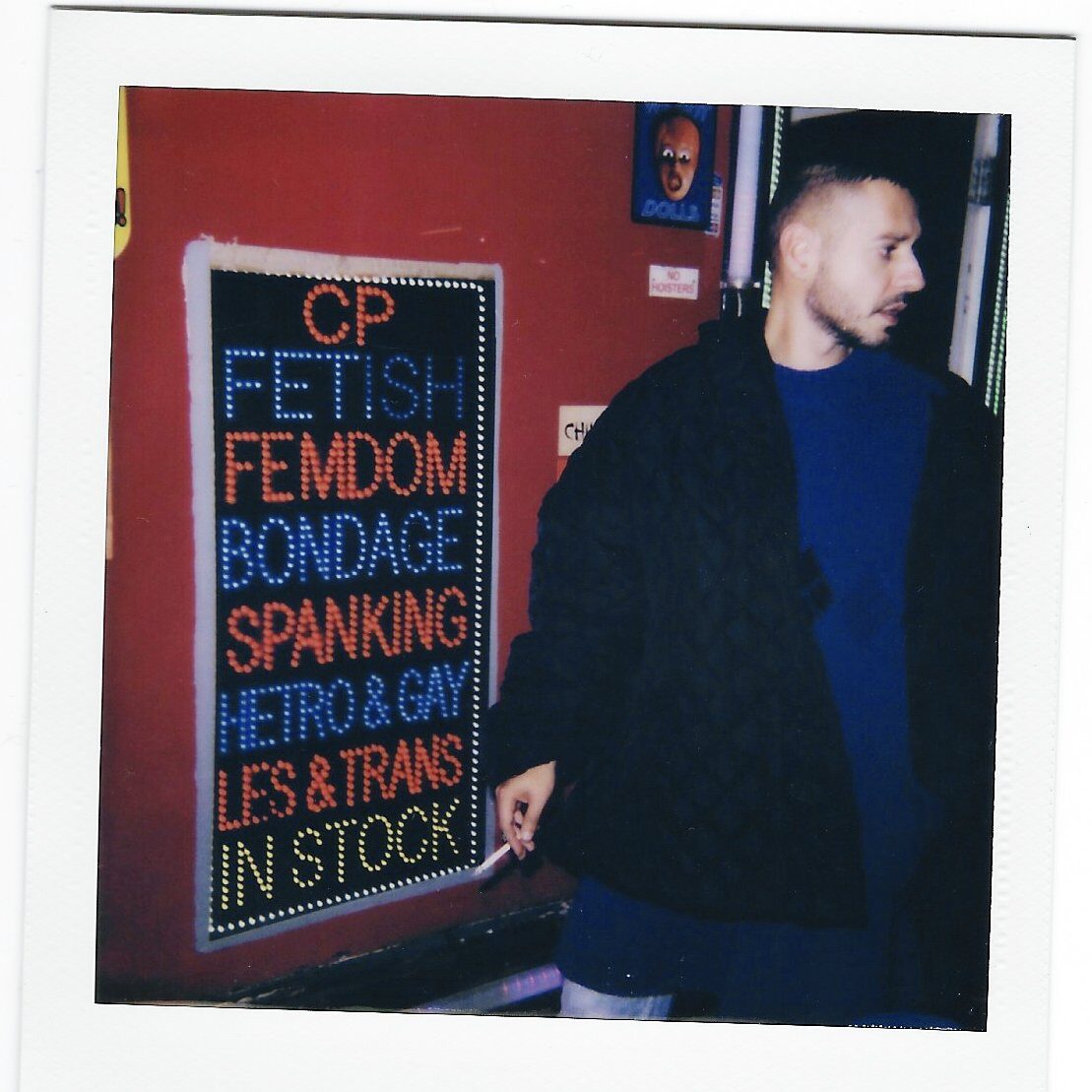

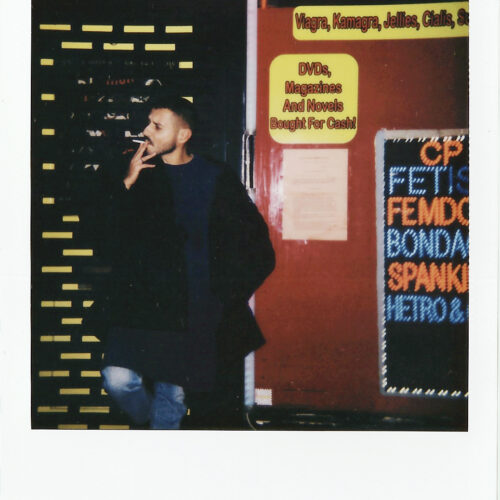

Late ‘90s: Brewer Street was the seedy underbelly of London’s Soho, where advertising pimps mixed with actual pimps, both knowing that sex sells.

Thankfully, for the sake of seedy underbellies, the pimping still happens. Early 2000s and thankfully, before Pret moved into the area, Stavros Karelis, founder of Machine-A, took a punt on a retail space that used to sell cakes decorated with cocks and knockers and that was a landmark meeting place for dealers for all sorts. I like to imagine that these tradesmen and women made business deals over a pot of earl grey and a cock shaped scone.

Unintentionally, but equally as intimidating as Soho’s porn shops, Machine-A opened its doors with a collection of clothes you couldn’t get anywhere else, supporting designers you’d never heard of. These were the days when Soho lost the likes of Pineal Eye, that unknowingly, passed the baton to Machine-A– the new savior of independent fashion and subculture. At the time, misunderstood and revered in equal measure, as all pioneers are.

Now that fashion has caught up to Machine-A’s future vintage vision and similarly to Byronesque, I talked to Karelis about the beginning of Machine-A and the happy ending that we call Machine-B.

Gill: Take me on an imaginary walk around your Soho.

Stavros: There are things that I find very familiar everyday I walk in Soho; and there are things that are new to me. What I mean is that I’ve been walking the same route for 8 or 9 years, so I’ve seen it changing quite a lot. What I loved and was obsessed about is that it was so unique, raw, and almost unpolished in a great, great way. I felt it was a very cultural and free place to be. I like that sort of freedom. You almost see people leaving their worries or concerns behind when stepping into Soho.

Gill: Was there somewhere else on the table for Machine-A, or was it always Soho?

Stavros: It was always Soho. I mean, it wasn’t the most strategic decision 9 or 10 years ago–I’m not a genius of real estate. When I started looking for spaces, I wanted it to be somewhere essential. I could never afford to be in any of the places like Bond Street and the areas I could afford weren’t resonating with me. From that point and onwards, I started thinking about Soho. I love the energy. I like the vibe. It was centrally located, but it wasn’t a shopping destination—that was a bigger challenge.

Gill: What other shops were here at the time?

Stavros: There was only the rumor of Supreme opening, basically, that was it as much as I remember on our street. There were the little independent stores, but not really anything fashion.

Gill: And how did the locals take to you?

Stavros: I feel with curiosity, initially…

Gill: Who were the locals?

Stavros: The locals here were at the massage spaces next door to us in both directions.

Gill: How official were these massage places?

Stavros: They were quite official. I mean, at the place to my right side, the owner was very suspicious of what I was doing. When I asked him for access to the space for our construction, he didn’t want us to see inside his building.

Gill: You should have just booked a massage.

Stavros: I know! I would’ve had all the information I needed. On the other hand, everyone was super friendly. To be honest with you, a few months after the store’s opening, they saw the people who came into Machine-A and became super curious. After a while, they really supported us.

Gill: Did the drug dealers and sex workers become your friends?

Stavros: Yes. Initially, we didn’t even have the shutters in front of our space. The question that everyone asks me is ‘Why do you want to be so exclusive and always have your door shut?’ I always said it wasn’t about exclusivity; it was about safety. We had to keep our doors closed all the time because outside of the store became popular for a lot of the peculiar types of Soho who did anything that you could imagine at any time of day.

Gill: Like what?

Stavros: Oh my god, from drug addicts to drug dealers to curious people that were coming to Soho to experiment. It was all happening right before our eyes. They were dealing outside of the store basically.

Gill: So, Machine-A was a landmark meeting place?

Stavros: They didn’t recognize the name, but they recognized the spot because there’s this triangle in our door. This little part in front of it became their spot because they couldn’t be seen from the main street. So, they would come and hide in there to do this. Eventually, I had to go out and ask them not to do that here. That’s how I became friends with them. Slowly, they saw that I wasn’t aggressive to them or ever called the police. I just very politely asked them to respect that we’re a new business and we don’t customers to be afraid to walk through the door. They took it really well. What’s funny is that when new people would come in the street to do something, the old people would come and say, ‘No, not in front of this store.’

Gill: What was Machine-A before it was Machine-A?

Stavros: It was Patrick Cox Cupcakes. He wanted to create cupcakes that were very sexual. I’ve only seen it once inside. It was a loud, very disco, gay type of shop in Soho. It was open for about one and a half years, and then he shut it down. That’s when I took over. When we started, we had to change the ceiling and all the space inside. The funny part about the ceiling is that once we started bringing it down, you could see all the layers of the previous businesses there before us. I wish I had taken a picture because it was very interesting. I remember looking at that ceiling and thinking ‘I’m going to become one of those layers here. How long am I going to last in this space? Am I going to be another layer of that history?’ I feel like we added our own layer.

Gill: You’ve told me before that Soho wasn’t right for the type of brands you wanted to carry. What brands did you start with?

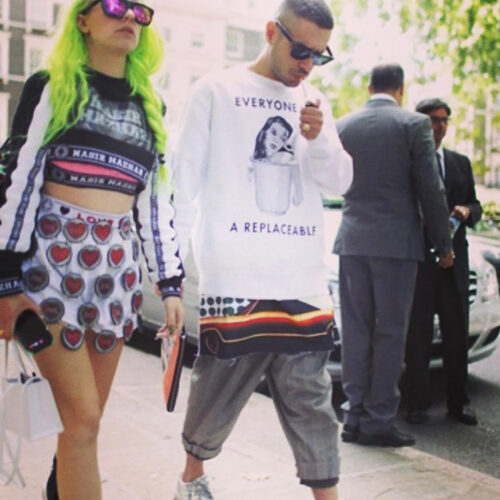

Stavros: There’s a big, interesting list of designers. For example, Nasir Mahzar. He was one of the designers that I absolutely loved, and I think he was a genius of his time. He’s still doing it but doing it his own way. It was Nasir, Ambush, it was all these designers that were just starting out.

Gill: When did you discover him?

Stavros: He was great friends with Anna Trevelyan. Anna was styling his look books. It was a moment when streetwear was just starting. It was the movement with Hood by Air and Nasir in London. We’re talking about that time when every single person on the streets and in the clubs were wearing the bully cap from Nasir. It was a moment of recognition that signaled we all belong in the same circle, but you couldn’t find it at any stores.

Gill: How did people find it?

Stavros: They bought it directly or they were friends who asked for it. He could have become one of the biggest designers if he wanted to. We managed to get many great brands because of one brand: Raf Simons. I was a huge fan of the brand. I made an appointment six months before I opened Machine-A, when there wasn’t an idea or understanding of what Machine-A was about. So, here’s this young guy walking into the big brands and telling them that we will be selling from graduates to big brands. Everything is going to be mixed in a way where you won’t have a dedicated space, and we don’t separate or divide the store into womenswear and menswear. The sales directors looked at me like a freak.

Gill: Why did you decide to do that?

Stavros: I wanted to have a mix. Initially, when we started the store, other people were doing it differently. For me, it had to represent who I was. I knew I had to be true to myself to support it. The way I dress is a mix of young, cool designers and some iconic designers like Raf. It wasn’t that I wanted to recreate my wardrobe for the store, but it had to reflect who I am. When I went to Raf, he really gave me the inner strength to understand that what I was doing might not be for everyone, but the right people would appreciate it.

When I went to Raf, they never asked me how big my store was like other showrooms do. Bianca Quets Luzi asked, ‘You like Raf Simons? I said yes. She said, ‘Ok, if I were to give you the brand, could you make a selection right now for me to see?’ It was a test. After I explained the concept to her, she put me right to the test and said, ‘If you want it, show me what you can do with it” and I found this very honest. She was smart enough to understand we were creating a new, young-oriented destination. I was shaking making my selection, taking piece by piece from the runway like it was Squid Game. After I made my selection, she went back in the office, came out, and said, “you have the brand.”

Gill: At the time, looking back, did you ever think that you were buying future vintage?

Stavros: No. It’s a bit embarrassing, but I didn’t connect that brilliant concept until I met you. You made me fall in love with this part of my work. You gave a different meaning to what I was doing. That’s why it’s so special, [what you and I announced], because after years of doing what we’re doing, there is now a much different connection of what I do and what you do. You gave me the concept of future vintage and for that I will always be grateful, because now I understand what I’m doing for the future.

Gill: Machine-A is intimidating. I remember it was, the first time I went in there. You say it wasn’t intentional, but who do you think you’re keeping out?

Stavros: That’s a tough question. When we first opened Machine-A, I wasn’t this mastermind sitting in my home thinking, ‘I would create this because it would be the unique concept.’ It was very much a life thing, and it was taking shape as it we were going along. In the beginning, we didn’t know who the consumer was, so of course you open your doors to everyone to experiment, to experience it, and to learn about it. I realized, sometimes customers would come in and would be very disrespectful, very dismissive.

Gill: Of what?

Stavros: They’d come in, look at it, and say, ‘I don’t get it, I don’t understand it.’ They would laugh. It hurts you because you see it as your baby, and you know what’s gone into it. I would become defensive about a designer. Information, knowledge, and education come along the way, but don’t dismiss something that you don’t understand. I was even more inclined to not educate them, but I wanted to inform them that this designer spent years in university, did this collection all by themselves in a studio space, working almost everyday to be able to put that product here. Then a big brand took over and copied half of it. I’ll tell you who I’d to keep out, I’d keep out some of the people from our industry who are lazy at doing their job. They come to discover. That upsets me because sometimes there’s a good way to do it: in a direct way. Some would come and acknowledge me, because we all know each other in this industry, more or less. They would ask me to show them what I have, or who they should have their eye on. And I would show every single item because I’m that type of person. I’ve never believed in exclusivity. I’ve never believed in holding something back. On the contrary, you see teams coming in and taking pictures. I know they are copying the whole thing or copying the designer or copying the vibe. I don’t like when that happens. I don’t find it sincere or honest. That’s why in the end we said no pictures of the products.

Gill: When you decided you were going to take the leap and start Machine-A, what was going on culturally that you either wanted to embrace or reject?

Stavros: I remember that there was a bit of time, when I first moved to London, that was like discovering the whole world. Clubbing, going out from Thursday to Sunday every night…. there were so many good nights. I would see everyone at the door to those events fully dressed up.

Gill: What were you wearing?

Stavros: It was the period of Hedi Slimane for Dior, and I was obsessed—it was his first or second season coming out. It was unseen at that point, the whole shape, the whole energy, the whole vibe. And I wore a lot of Nasir [Mahzar]. For me, that was a completely eye-opening experience. I would meet all these designers on the dance floor. This is where I met them. I didn’t see them at university because I was studying international law. I would see them in the clubs and ask what they were wearing and where can I see and buy their stuff? And they’d say nobody is buying them. I started thinking, ‘What the fuck? There is no space? No one is selling this?’ That’s where it started as an idea.

Gill: Name drop. Who were the early supporters of Machine-A?

Stavros: Apart from Anna Trevelyan, who was such an integral part for me launching Machine-A—don’t forget that at that point, Anna was the first assistant of Nicola Formichetti, working with Gaga when she was at the boom of her career. It was all about her, all about Beyonce, so she created this very cultural thing in terms of celebrities and influences—we connected with Nick Knight. Showstudio and Nick Knight eventually became partners with Machine-A. I’m so grateful for Nick, not just because of the brilliant person he is, but Nick partnering with Machine-A… No one knew what Machine-A was about internationally. But everyone knew who Nick Knight was and what Showstudio is about. Suddenly it was like, ‘What is that store in Soho that is partnering with Nick Knight and Showstudio?”

Gill: What do you think Nick saw?

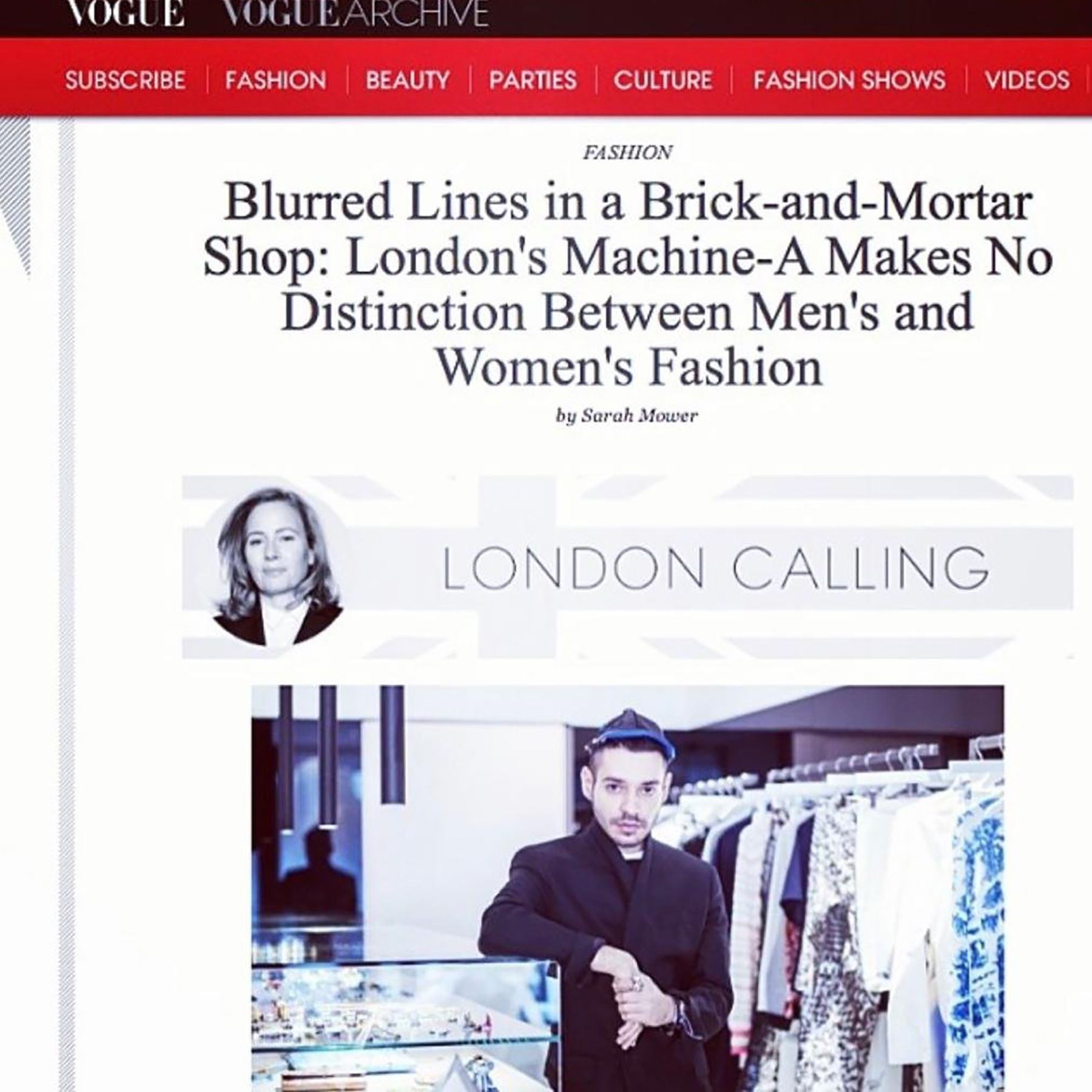

Stavros: Nick saw the love and passion in terms of emerging designers. Nick is one of the biggest advocates of young, talented people. He works with the Dior’s and Chanel’s and Kanyes’ of the world, but he worked with Alexander McQueen when he was starting out, he worked with John Galliano when he was starting out. He was always trying to find those people that he really believes in. He’s a great advocate for young, emerging talent. When he saw Machine-A, he saw this incredible creative hub of energy and fashion, and he felt this is the future of fashion. The way we connected was because Nick was doing a project about the iconic shops that changed the history of fashion in London. Obviously, it was Westwood and all those moments, but in his selection, he included Machine-A as the current store that changes fashion as we know it in the history of London. So, that’s how we connected. Then, there was Sarah Mower. She walks into Machine-A and talked to me for 45 minutes. I had to explain every single designer to her and what I was doing with them. She wrote a really great review of Machine-A for US Vogue. After that, everyone started coming here asking for an interview. These were the people who established me in the early stage. Now I am so honored and grateful to be partners with Tomorrow and Stefano Martinetto, Giancarlo Simiri and Giovanni DeMarchi who are leading the way to establish MACHINE-A on a global level.

Gill: The establishment supporting the anti-establishment…There still isn’t anything like MachineA. You’re the only store like it. Nobody has successfully copied you. Why do you think that is?

Stavros: I think the nature of what we do is very difficult. I don’t want people to think everything has been roses, along the way.

Gill: What was the hardest thing?

Stavros: Establishing a busines that’s commercially successful. As a creative, you have great concepts in your mind, great people around you, but at the end of the day, it’s fueling the business, being self sufficient, and being able to carry on. Also, establishing your customer, understanding the market, changing when you need to change, but holding your guns when you need to hold your guns.

Gill: What did you need to change?

Stavros: A store like Machine-A that is on the front line of recommending the trends and recommending who to watch can get confusing, because if you try to jam in every single trend, if you try to represent the whole industry, you will eliminate what is special about you. I’ll give you an example: when we’re on the second, third, and fourth years of Machine-A, we’re talking about a period where there was a boom in the market for brands like Off-White and Vetements. This is a street where you already have Palace and Supreme. I always say you have to think about the consumer because the consumers and customers are attached to trends, and they can easily move as the trends go along. It was very important to paint the core audience and focus on that because loyalty is something extremely hard to earn. Loyalty is going to carry you through all the times. Most of the time, it wasn’t the people that were following the trends that supported us. When our shop was shut down for 9 out of the 12 months during the Covid lockdown, it was the core community of loyal customers that said, ‘We love the store, we love the brands, we keep shopping from you even though you’re shut down’. And that’s what pays off after you’ve taken a difficult road. Because it’s been a very difficult road.

Gill: What was one thing Nick told you that you wouldn’t have done otherwise?

Stavros: I owe Nick, and our mutual friend Rei Nadal, the existence of Machine-A because—a lot of people don’t understand this—especially in those first two years, we came so close to not exist. In every business you’re establishing, the first two years are the most hardcore years. This is when most businesses shut down. Nick said to me, ‘What you’re doing is very important, and I can carry on next to you, but I cannot do it for you, so if you don’t do it, then I cannot support you, but carry on because what your doing is very special, it doesn’t exist at the moment, and if you find the strength to go through it would be great later on.’ And he was right. But at that point, I didn’t know if I could carry on doing it. He convinced me otherwise.

Gill: What would do if you weren’t doing Machine-A?

Stavros: I think I would be doing something involved in psychology, nothing in the arts or in the creative world. I would be somewhere very different, I think. Something involved in psychology. I think it’s an element where it can become a weakness to be like that, especially when you have to lead and make tough decisions, but it’s the people close to me, my relationships with designers, and the team at Machine-A who I would never be able to do anything without. They really are amazing people. And the reason why I think they tolerate me is and my nonsense is because of empathy.

Gill: What’s nonsense?

Stavros: Pushing in directions where sometimes they ask, ‘What the fuck are you doing? You’re pushing too much’ but that’s because I see the bigger picture and I have to move it there. To grow as a company, you have to think about the changes of the present moment, and you have to always think about what the future is about. Sometimes that understanding is difficult, and they challenge me. I like that. Sometimes they’re right.

Gill: What did they think when you said we’re bringing in a load of old clothes?

Stavros: They loved it. They love the concept because two very close people that I work with come from this vintage and archive background. They absolutely love it. I’m actually the least knowledgeable for the first time.

Gill: What are your favorite pieces from the Byronesque collection?

Stavros: The tie pin from Margiela. I’m obsessed with that piece. The Rick Owens blue shirt, obsessed with it. I also love the grey and white Rick bomber. From Gareth, I really love his black and white tile leggings collection because I remember it was one of the first collections I saw at Dover Street Market, and at the time DSM was my mecca. I would go almost every other week, and I remember holding those leggings because they were so iconic. And Asfour. I wish I would fit into those trousers. They are absolutely iconic, but they need someone tall and beautiful. The bags are iconic. And I now trust what you said to me in terms of those bags because when I saw them in real life, I was like, “fuck this is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen,” and I can tell how many designers have been inspired by this brand. From Raf Simons, there’s the suit in there with shorts. Its very good. Its very me.